Moving beyond 'fun': A designer's guide to emotional granularity

How might game designers unintentionally encourage players to do evil? And can you feel gratitude in a racing game?

Have you ever wondered why some games make you feel like a hero, while others leave you feeling guilty about your choices? Or why certain mechanics can evoke such strong emotional responses that you remember them years later?

Throughout my career, I've become fascinated by the psychological side of game design—how we can intentionally craft experiences that evoke specific emotions in players.

Today, I want to share a story that changed how I think about game design, and then dive into practical ways you can expand your emotional palette as a designer.

The Journey That Went Wrong (And Then Right)

Let me start with a story about one of the most beloved games of the last decade, though you might not recognize it from how it began.

Once upon a time, there was a game development team with an ambitious goal. They asked themselves:

"Can we have an online game where people feel friendly and compassionate towards each other?"

This was no small challenge. Anyone who's spent time in online multiplayer games knows how toxic they can become. But these developers were determined to innovate how it feels to play with strangers from the internet.

They created a prototype with what seemed like perfect cooperative mechanics:

Players could push each other to help them reach higher platforms

Once up, the other player could pull their companion up to safety

The goal was to incentivize positive cooperation between players

Sounds wholesome, right?

They put this prototype to a playtest, eager to see their vision of compassionate online gaming come to life.

What was the result?

Players chose violence.

Instead of the intended cooperation, players preferred pushing each other off cliffs. They found a way to kill each other using the very mechanics designed to promote friendship.

Faced with this outcome, the developers asked themselves a darker question:

"Is humanity at its core just dark?"

The answer, thankfully, was no.

The developers realized something crucial: It wasn't the players' fault how they behaved. Players' behavior was shaped by the tools they were given.

Players experiment with what they can do and repeat actions that lead to something interesting. When pushing someone off a cliff caused a dramatic reaction, it became more engaging than the subtle satisfaction of cooperation.

This game eventually became Journey, one of the most celebrated examples of positive online interaction in gaming history. But how did they fix it?

The developers made two key changes:

Removed the reward by disabling collisions between players

Added a different reward for being close to each other (getting energy and being able to fly)

This completely transformed the game. Players started staying close to each other and expressing positive emotions towards one another, all without using words.

It's a perfect example of how game mechanics can reinforce certain emotions, and how even negative interactions can be unintentionally caused by design.

(The clip above comes from this great tutorial video made by avaloki)

Game Designers Are Emotional Chefs

This story illustrates something profound about our role as game designers. We're not just creating systems or mechanics—we're crafting emotional experiences.

As Tynan Sylvester beautifully puts it in "Designing Games: A Guide to Engineering Experiences":

"Just as a skilled chef can deconstruct a complex dish into individual flavors, a game designer must be able to sense a flicker of anger, a pulse of triumph, or a dash of disgust."

Game designers, like chefs, need to understand their ingredients—but instead of salt and spices, we work with emotions.

Why do we play games?

Think about it: Why do players spend energy, time, and money to chase a ball, move tokens on a board, or click pixels on the screen?

Emotions are the reason that games exist.

As Tynan Sylvester put it: "The primacy of emotion is one of the great unacknowledged secrets of game design. Ask anyone about a game and they'll tell you what they thought of it. They'll make some logical argument about the game being good or bad. But usually that logic is just an automatic rationalization for the emotions underneath. What really matters is how a game makes us feel."

The Emotional Vocabulary Problem

Here's where it gets interesting. The English language alone has about 3,000 words for emotions. Some emotions are easy to recognize, like anger or fear. Others are more subtle and often difficult to name.

Consider these examples:

Lugubrious - exaggeratedly or affectedly mournful

Ebullient - energetic, enthusiastic, and excited

Chagrin - anger or disappointment caused by something that doesn't happen the way you wanted

And some emotions' names are even unique to a specific language!

Saudade - Portuguese term for bittersweet nostalgia or yearning

Hiraeth - a Welsh word for deep longing for a home you can't return to

Schadenfreude - a feeling of pleasure when something bad happens to someone else

The ability to differentiate and name emotions is called emotional granularity. It's like the difference between someone calling a wall "blue" and an interior decorator who can distinguish between azure, navy, cerulean, and cobalt.

Developing high emotional granularity has several benefits for mental health. Two decades of research show that people with high emotional granularity are less likely to resort to unhealthy strategies like binge drinking or aggressive behavior.

But besides having a positive impact on mental health, emotional granularity can also make you a better game designer.

The more precisely you can identify and name emotions, the better you can craft experiences that evoke them intentionally.

And how do we, game developers, usually talk about emotions in games? What are the most commonly used words when it comes to analyzing the emotional state of players?

IT'S FUN.

(Or not)

When it comes to emotions in video games, the industry often still behaves like teenagers who struggle to communicate and understand their emotions. Even when we go beyond "fun" (or "cool"), we tend to focus on just a few basic emotions like anger, fear, or joy.

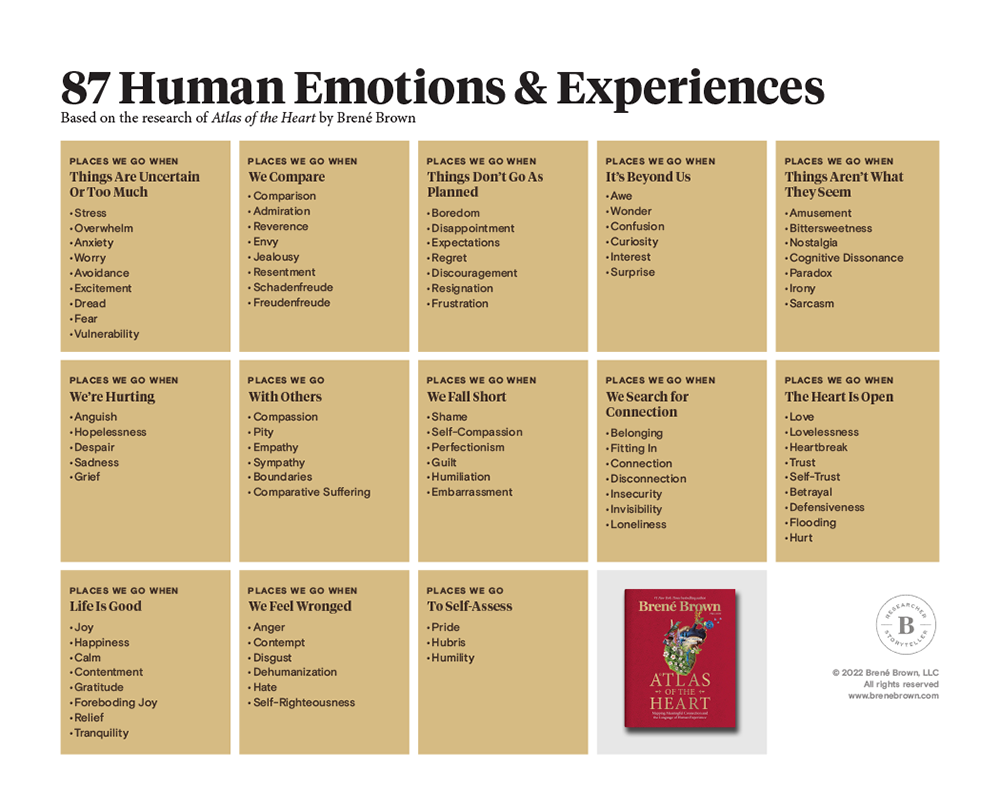

But take a look at any list of emotions (e.g., from Brené Brown's "Atlas of the Heart"), which maps out dozens of nuanced emotions across different categories. We have so much more to work with!

Just as a painter needs more than primary colors to create compelling art, game designers need to expand beyond basic emotions to create truly memorable experiences.

Why is this worth the effort?

Better control over the purpose of your design

Great source of inspiration to make something unique and innovative

Market opportunities by identifying emotions that people often seek but that are underrepresented in games

Consider the rise of cozy games in recent years. Before Stardew Valley, there weren't many games focused on providing peaceful experiences. Publishers were avoiding such genres, but it turned out there was huge demand for games that made players feel calm, content, and connected to simple pleasures.

Emotion Through Mechanics: Practical Examples

Here's where games truly shine compared to other media. While cutscenes, text, and visuals can provide emotional moments using tools from movies, literature, or paintings, the real power of video games is interactivity.

As Will Wright, designer of The Sims, noted:

"People talk about how games don't have the emotional impact of movies. I think they do—they just have a different palette. I never felt pride, or guilt, watching a movie."

Emotions provided by game mechanics are more powerful, and players will remember them longer, especially when they feel that the situation was unique and came from their own actions.

Let me show you briefly how different emotions can be evoked through specific game mechanics:

Sense of Loss

XCOM: Enemy Unknown - The permadeath feature makes you genuinely care about your soldiers. Losing a veteran fighter you've grown attached to creates real grief.

Before Your Eyes - Uses eye-tracking technology where blinking advances time. You literally can't hold onto precious moments—they slip away with every blink, creating a profound sense of loss about time passing.

Anxiety

Amnesia: The Dark Descent - Removes combat entirely to invoke anxiety. When you can't fight back, every encounter becomes terrifying.

Hellblade: Senua's Sacrifice - Uses a brilliant psychological trick. The game warns players that dying too many times will permanently delete their save file. This creates genuine fear of death—though it's actually a bluff designed to mirror the psychological fear experienced during psychosis.

Guilt

Papers, Please - Creates moral dilemmas through its core mechanic. Checking documents thoroughly saves innocent lives but earns less money for your starving family. The mechanical tension between accuracy and speed creates daily moral crises.

This War of Mine - Resources are limited, forcing you to choose between your group's survival and helping other people. Will you steal medicine from a sick family to save your own companions?

How to Choose Emotions for Your Design

When designing with emotions in mind, ask yourself:

What is the main emotion that your game uses?You can establish core emotions the same way you establish design pillars. They serve as a beacon for the rest of the creative process. It'll help you understand what your game is really about. Is it about grief or satisfaction from revenge? Do you want to tell a story about betrayal or trust? Or maybe it's about belonging and relatedness?

Should this feature reinforce that emotion or provide some variety?Remember, you don't need to always target the same emotion. Contrast is a powerful tool—emotions appear more powerful when they're unexpected and opposite from what we just experienced.

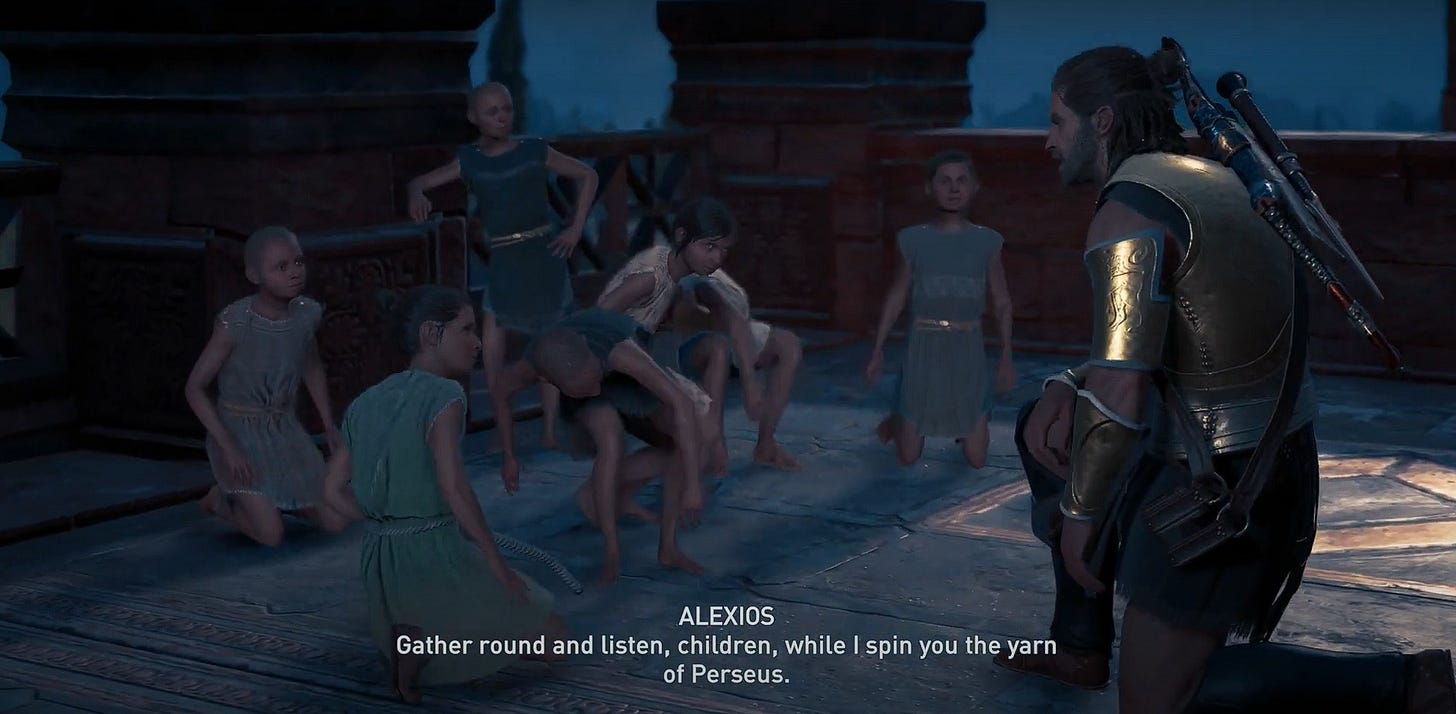

A good example of such contrast is the "A Treasury of Legends" quest from Assassin's Creed: Odyssey. The core loop of this game is focused on violence and combat, but in this side story, your task is to tell children the story of the legendary hero Perseus. The player can first learn the story from a nearby room with many relics related to Perseus, and then try to tell the story by selecting the correct options.

The quest is structurally quite simple but really stands out compared to usual activities in the game. It's surprising, introduces some comedy relief—especially when you don't remember answers. And when you do, you can feel like a mentor or teacher, which is not the usual feeling in an action game.

Should the emotion be positive or negative?When deciding between positive and negative emotions, remember that you don't necessarily need to avoid negative emotions. Games provide a testing ground for social interactions and real-life skills. Sometimes exploring difficult emotions in a safe environment can be valuable.

The Risks

There's always a tension between commercial risk and artistic challenge.

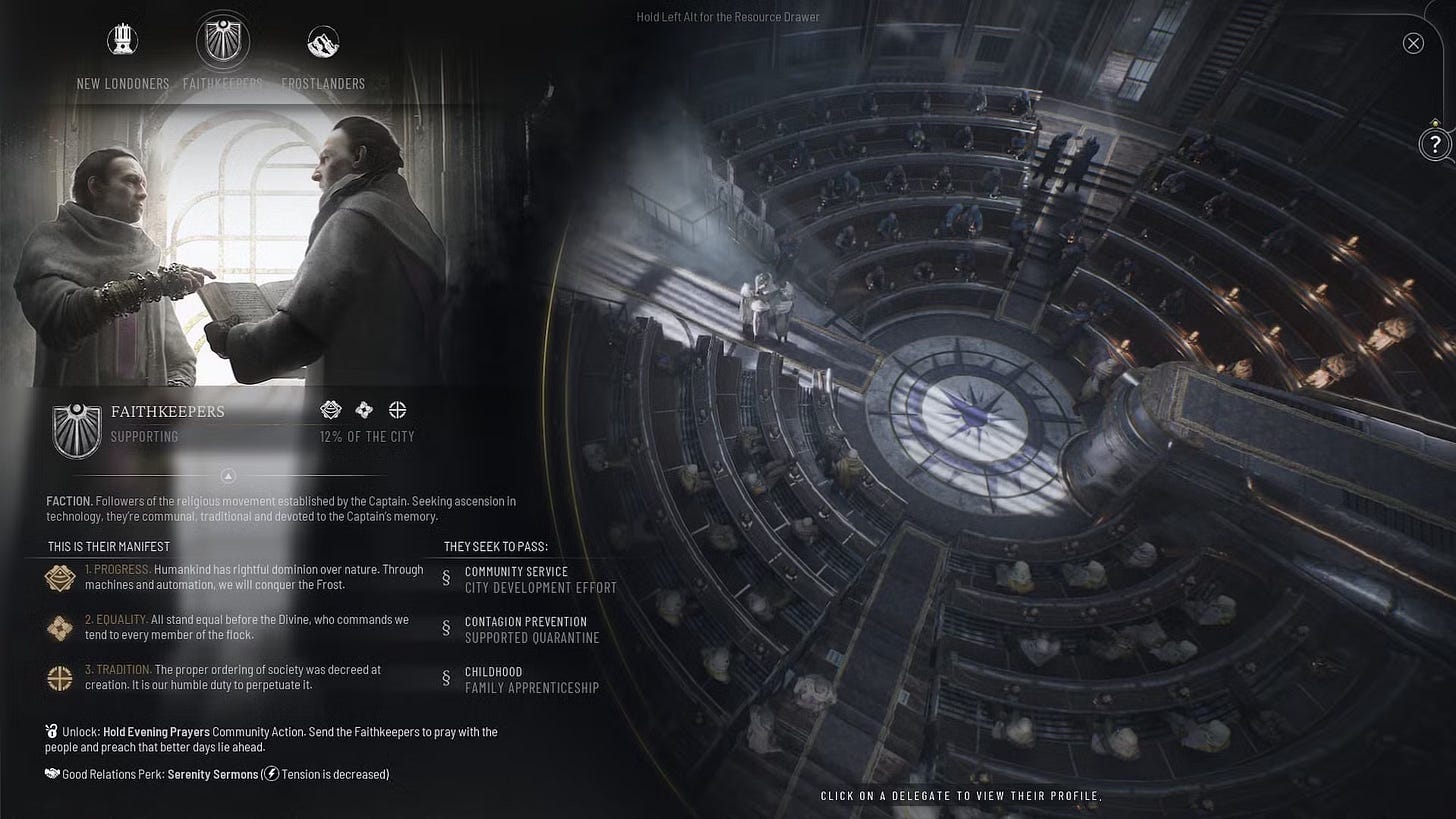

Mismatching player expectations about what they expect to feel versus what they actually feel can be problematic. For example, in Frostpunk 2, we introduced complex political systems that made it harder for players to feel like the savior of their city. Opposing factions try to push the city in different ideological directions, so most of the time, you need to balance and navigate towards a fragile compromise. You can understand the position of politicians, often hated for not fulfilling their promises or changing their views. This anti-power fantasy was appreciated by players and critics looking for a thought-provoking experience, but for those who wanted to feel in control, it was a frustrating experience.

Cultural differences also impact emotional response to game mechanics. For example, Chinese players were much more critical of the political elements in Frostpunk 2 than European or American players. They found the presented conflict more artificial and frustrating, as in their perception, a nation should be more united in the face of a crisis.

The key is setting expectations correctly through marketing, gameplay videos, and proper communication of your game's emotional fantasy.

Practice Exercise: Emotional Design

Here's a practical exercise to develop your emotional design skills:

Pick an existing genre or game

Randomly select an emotion from an emotional atlas

Design a mechanic that evokes that emotion

It could be either a main game loop or a smaller feature in a larger game

Test your results with players

Research examples in existing games

Let me show you how this works with a concrete example:

I prepared a simple spreadsheet to randomize the genre of the game and the emotion. You can use it here.

Genre: Racing

Emotion: Gratitude

Design:

Working title: "Kario Mart" (Inverted Mario Kart) ;)

Goal: Reach the finishing line

Gameplay:

A villain tries to stop all players with aircraft and traps

Players have limited lives; when destroyed, they're stuck on track

Other players can rescue them by driving close and pressing a button

Points are awarded for:

finishing by yourself (50pts)

any player finishing (10pts)

all players finishing (100pts)

When reaching the finish line, players can choose to stop or do another lap to help others

The game ends when the timer runs out or when all players are unable to drive (either they got destroyed or decided to finish the game)

This creates gratitude when someone risks their score to save you, and generosity when you choose to help others instead of securing your own victory.

Let’s look at other games that managed to evoke gratitude:

In Death Stranding, you can use structures built by other players. Whenever you struggle with climbing a mountain and find a useful ladder left by somebody else, you can show gratitude by leaving a like. Just like in social media, but without any possible toxicity!

Nier: Automata managed to make players feel gratitude in one of its endings. If you are not afraid of spoilers, I recommend reading this great piece about probably one of the most creative endings in video games ever:

Key Takeaways

Learn to identify and name emotions using resources like "Atlas of the Heart"

Think about which emotions you want to evoke when designing

Playtest to see actual reactions rather than assumptions

Set player expectations regarding your game's emotional content

Exercise your skills regularly with emotional design challenges

Final question

We have the tools to make players feel anything we want them to feel.

The question is: What feelings does the world need more of?

As game designers, we wield tremendous power over human emotions. Every day, millions of people spend hours experiencing the feelings we craft into our games.

What will you choose to make them feel?

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this deep dive into emotional game design, subscribe to get more insights on creating games worth your time. What emotions do you think are underexplored in current games? Let me know in the comments.

Further Reading

Tynan Sylvester, "Designing Games: A Guide to Engineering Experiences"

Katherine Isbister, "How Games Move Us: Emotion by Design"

Elizabeth Sampat, "Empathy Engines"

Scott Rigby & Richard M. Ryan, "Glued to Games: How Video Games Draw Us In and Hold Us Spellbound"

Brené Brown, "Atlas of the Heart: Mapping Meaningful Connection and the Language of Human Experience"

https://www.theverge.com/2022/3/13/22972989/journey-10-year-anniversary-multiplayer-jenova-chen-austin-wintory

Great read! Especially liked that bit of info about Chinese players in Frostpunk 2.