The "Bad" Game That Taught Millions About Life and Death

From Indian spiritual metaphor to children's board game: the surprising journey of Snakes and Ladders.

Imagine pitching this game to a modern publisher:

"Players have no strategic choices whatsoever. The game length is completely unpredictable—it could end in 15 minutes or drag on for hours. Success depends entirely on luck, and players get brutally punished for rolling the wrong numbers. Oh, and there are more possibilities to fail than to succeed."

You'd be laughed out of the room.

Yet this "terrible" game design has survived for over 700 years, crossed continents, and taught millions of children around the world. You probably played it yourself: Snakes and Ladders.

But what if I told you that every element you might consider a design flaw was actually intentional? That this seemingly simple children's game was originally a sophisticated rhetorical device designed to teach profound religious principles about life, death, and the path to enlightenment?

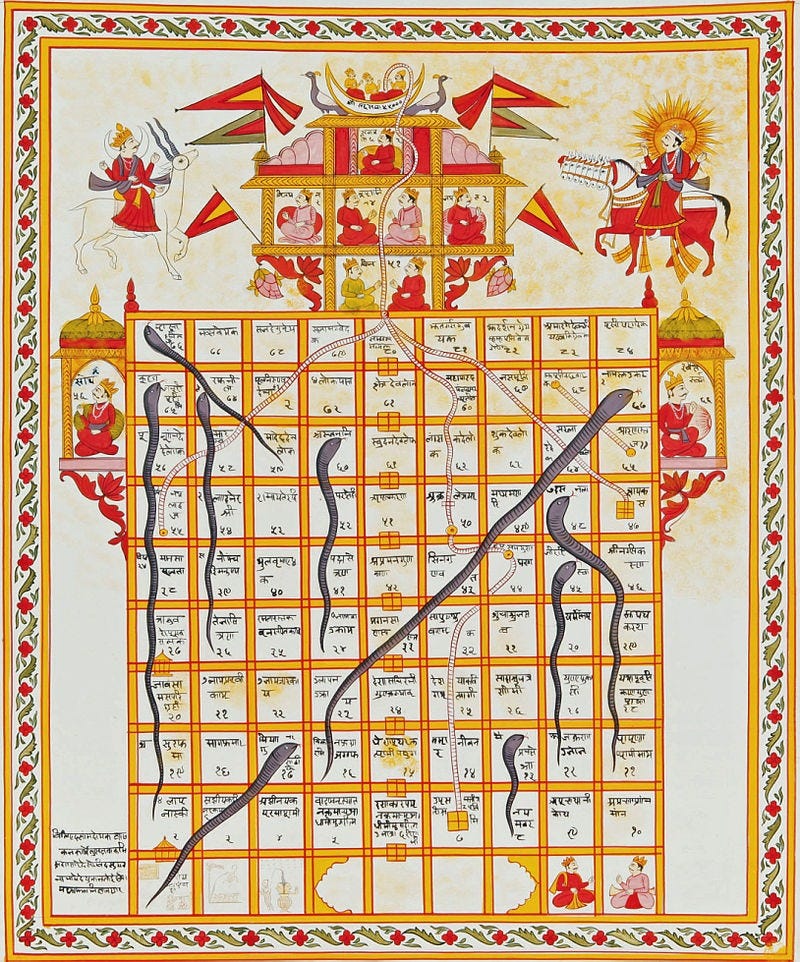

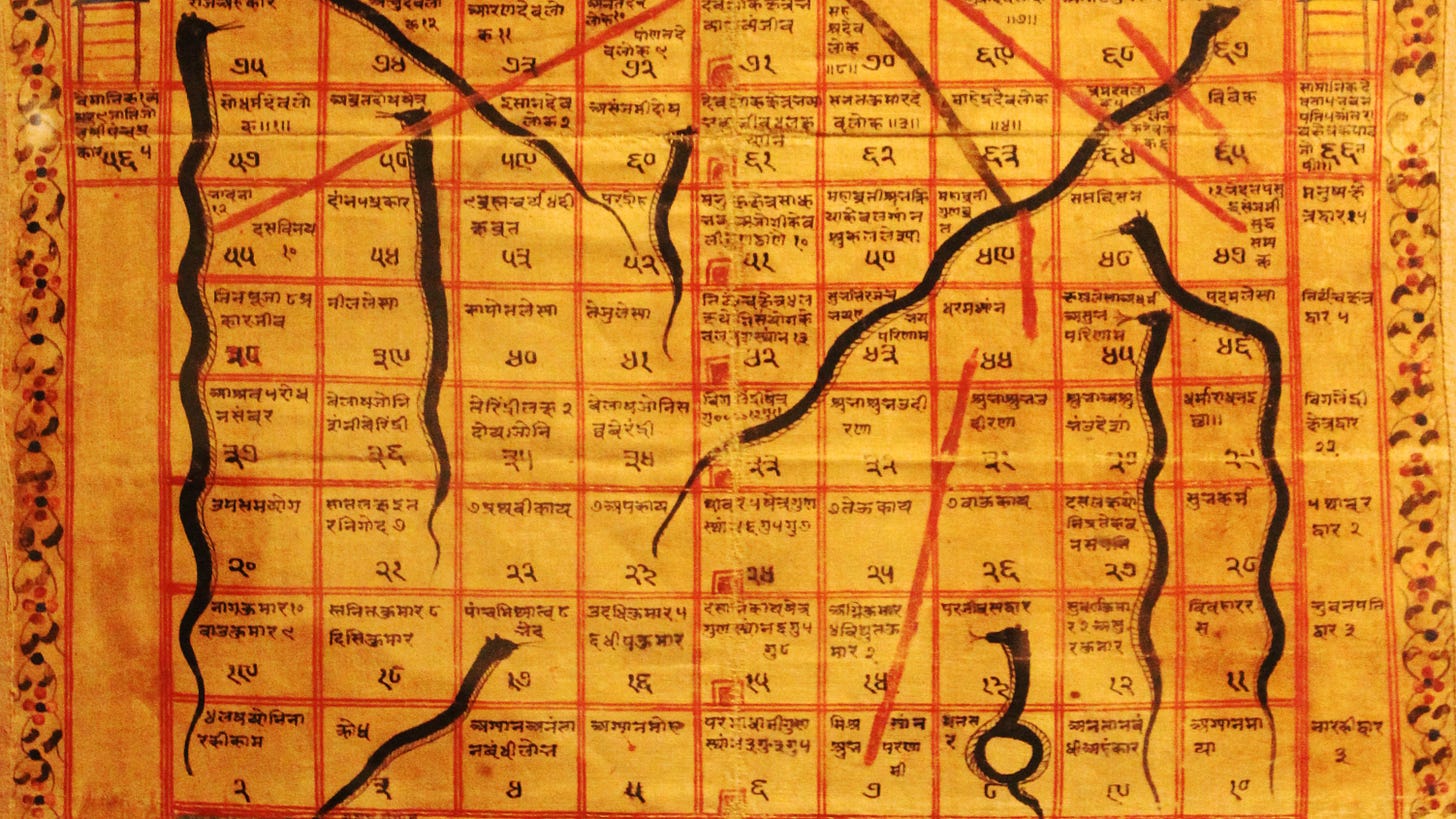

Snakes & Ladders didn't start as a children's racing game. In its original form, it had a much more respectable name: gyan chaupar - literally "the game of knowledge."

The origins remain debated, but the game is closely tied to religious purposes in medieval India. According to one version, it was designed by Dnyaneshwar, a thirteenth-century Marathi saint. The act of playing wasn't just entertainment - it could be part of religious rituals, such as during the Jain Paryushan festival, when devotees fasted and played the game as a form of spiritual engagement.

In the original gyan chaupar, every element carried deep symbolic meaning. Players started at square 1, representing birth, and aimed to reach the final square, which represented moksha, a release from the cycle of death and rebirth. That’s why the game was also known as Moksha Patam, which could be translated as Path to Liberation.

The ladders weren't arbitrary shortcuts. Each one represented specific virtues like faith, reliability, generosity, knowledge or asceticism

The snakes weren't just obstacles—they embodied vices that drag souls backwards: disobedience, theft, rage or greed.

The entire mechanic was a religious metaphor. Ladders and snakes represented karmic behaviors, either helping or hindering a player's journey toward spiritual liberation. Every roll of the cowrie shells (the ancient equivalent of dice) determined whether your actions led to spiritual advancement or moral regression.

Here's where it gets fascinating from a design perspective. Players have almost no agency over where their pawn lands—they simply roll dice and move accordingly. From today's game design standards, this looks like a fundamental flaw. We've been taught that player agency is crucial for engagement.

But this "flaw" was actually the game's message: you need to align with your fate.

Some versions took this philosophy even further by prescribing a "correct" order of spiritual progress. As one Map Academy notes:

"In some boards, there was a prescribed order to a player's moral progress, meaning that a sudden ascension to a particular square (such as Brahmaloka, or the abode of Brahma) had to be followed by a descent from a subsequent square down a snake (to prithvi, or earth) at least once in the game."

Players were required to land on such squares with an exact roll - you couldn't simply skip past important spiritual lessons.

The game's balance revealed another profound insight. The number of snakes was typically higher than the number of ladders—sometimes twice as many—and their effects were more punishing. This wasn't poor balancing; it was intentional design meant to illustrate a spiritual truth: the path to enlightenment is harder than the path to corruption.

Evil was easier to fall into, while virtue required more effort to achieve and maintain. The game literally embedded this moral lesson into its probability systems.

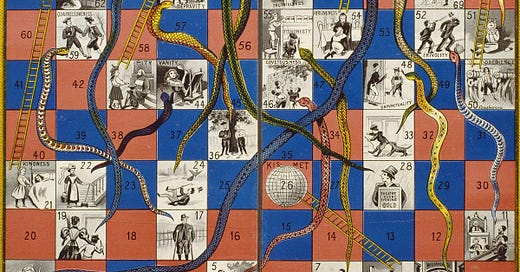

In the 1890s, gyan chaupar was brought to Britain and renamed "Snakes and Ladders." The mechanics remained intact, but the cultural adaptation was fascinating. The game lost its religious connotations while retaining the "good versus bad deeds" framework.

More interestingly, the balance changed. The English version featured equal numbers of virtues and vices. As the YouTube channel Extra Credits notes in their exploration of this topic, this shift may reflect differences between Eastern and Western religious philosophies - in English Protestant culture, the dominant belief was that every sin should have an opportunity for redemption.

Did you know that the phrase "back to square one" possibly comes from Snakes and Ladders? The earliest evidence of this phrase refers to the game: "he has the problem of maintaining the interest of the reader who is always being sent back to square one in a sort of intellectual game of snakes and ladders."

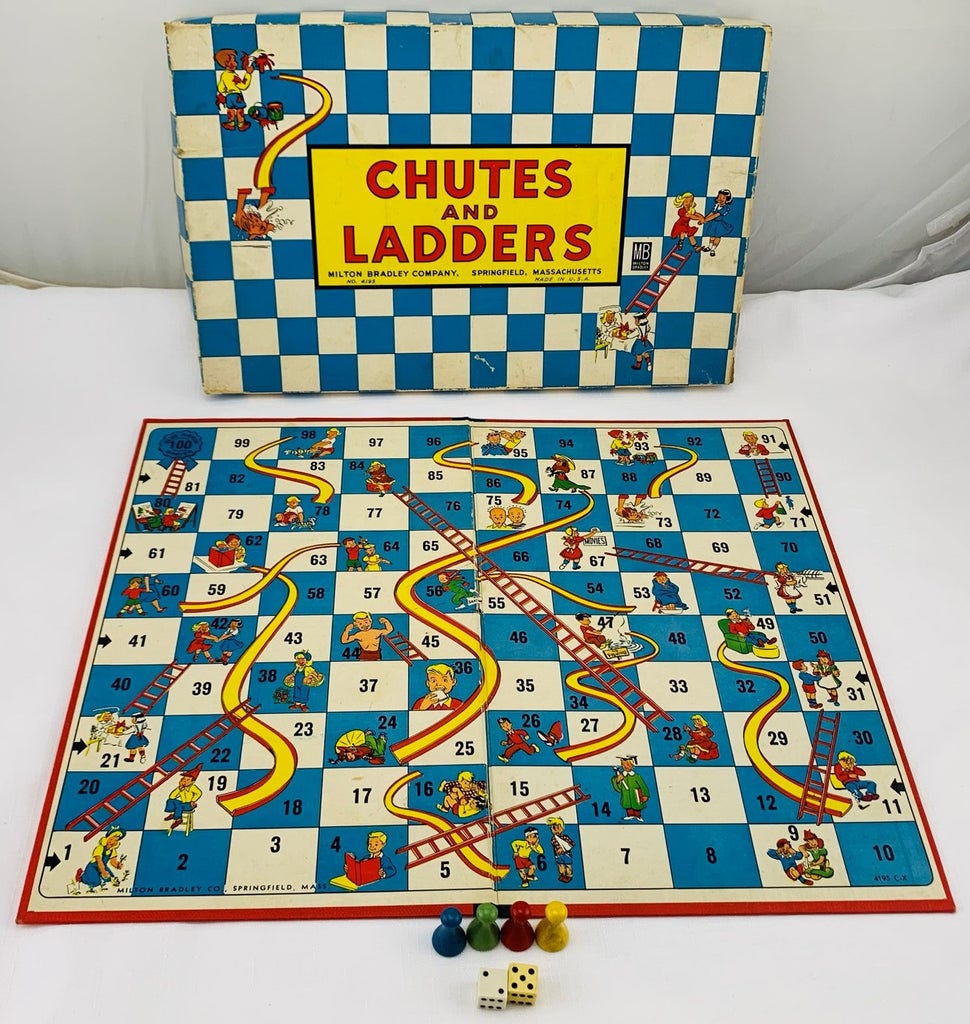

Later, in 1943, Milton Bradley created an American version called "Chutes and Ladders," replacing snakes with playground slides because snakes seemed too dangerous for children. The moral lessons remained, but now they depicted everyday childhood behaviors rather than spiritual concepts.

So why has this game remained popular and survived until today? The game is completely random and you can't even be sure when it will end—theoretically, it could take any amount of time, especially in versions where you need to roll the exact number to finish (if you roll too many, you bounce back from the last tile).

Easy to learn (and teach by it): The most obvious reason the game has survived is its simplicity—even very young kids can grasp the rules and find satisfaction in observing the effects of their die throws on the board. It also serves as a tool to familiarize children with numbers and simple math, adding educational value.

Production costs: It's cheap to produce—you only need a board, a few pawns, and a die (or other randomizer).

The thrill of randomness: While it makes the game pretty irritating in the long run, especially for adult players, for kids who don't yet have many other gaming experiences, it provides a genuine thrill of unpredictability. Will this throw make me ascend a bunch of rows? Will I roll enough to pass by the snake's mouth lying just ahead of me?

Imagination fills the gaps: As always with games—when you allow your imagination to work and engage with the game, you can forget about its flaws. The story your mind creates becomes more important than the underlying mechanics.

You can read more about why our minds love unpredictability and randomness in one of my previous articles.

Lessons from Snakes and Ladders

The survival of Snakes and Ladders teaches us several valuable lessons:

Sometimes "flawed" mechanics serve a higher purpose. What looks like bad design might actually be intentional communication of deeper themes.

Cultural adaptation doesn't require mechanical overhaul. The same core system successfully conveyed different messages across cultures simply by changing the context and balance.

Simplicity has its own power. In our rush to create complex, agency-rich experiences, we sometimes forget that simple, clear rules can be profoundly effective.

Randomness isn't always the enemy. While we often focus on giving players control, sometimes the experience of surrendering to chance can be meaningful in itself.

Snakes and Ladders raises a fascinating question for modern game designers: What are we really teaching through our mechanics?

Every game system communicates values, whether we intend it or not. When we design progression systems, difficulty curves, and reward structures, we're not just creating entertainment—we're embedding lessons about how the world works, what behaviors get rewarded, and what success means.

The creators of gyan chaupar understood this intuitively. They didn't just want to entertain; they wanted to teach. Every element of their design served their educational purpose, even when it made the "game" less traditionally engaging.

In our modern games, what values are we embedding? What behaviors are we rewarding? What view of the world are we teaching players through our mechanics?

The beauty of gyan chaupar wasn't just its longevity—it was its ability to package complex philosophical concepts into a format that anyone could understand and internalize through play.

As we build increasingly sophisticated games, perhaps we can learn from this ancient design: that sometimes the most powerful games aren't the ones that give players the most choices, but the ones that help them understand the choices they have in life.

You didn't convince me to like this game, but its origin story is truly interesting. Thanks for sharing your thoughtful analysis!