What do politics and game design have in common?

Should games be a politics-free zone? Or rather - all games are political, and there is no escape from it? And why you should care about it.

SimCity isn’t a game series typically perceived as political, especially when talking about the first entry in the series, released in 1989. This series has never been controversial; instead, such games are perceived as intelligent entertainment for everyone. Spending your time on planning, building, and managing was engaging for people of different ages or genders. Games from the SimCity series were sometimes even used for educational or learning purposes across the world.

Despite all of that, SimCity is political. In fact, there aren’t many games that are MORE political than SimCity.

Clayton Ahsley wrote a great article about how Jay Wright Forrester's book Urban Dynamics inspired Will Wright, SimCity’s designer. He mentions this book in the context of learning about how urban planning works.

What is it, exactly? Let’s read the official description:

“In this controversial book, Jay Forrester presents a computer model describing the major internal forces controlling the balance of population, housing, and industry within an urban area. He then simulates the life cycle of a city and predicts the impact of proposed remedies on the system.”

Sounds like a perfect handbook when you’re making a game about construction and managing cities, ain’t it? But wait, why does this description start from “In this controversial book…”?

This book influenced many government urban-policy decisions, and from today’s perspective, many of them are heavily criticized. Clayton Ashley provides us with examples:

“Forrester’s arguments enabled the Nixon Administration to claim that its plans to slash programs created to help the urban poor and people of color would actually, counterintuitively, help these people.

The book’s model was also very abstract. None of the people in the city belonged to racial, ethnic or gender categories and it left out any representation of the city’s geography, like neighborhoods or parks. When criticized by urban planners and anti poverty activists, Forrester would protest that his model was merely a tool for understanding how cities worked.”

What does it have in common with SimCity? As a game that shows a part of reality, it needs to make assumptions about how the world works. It says which solutions are better and which are worse. Intentionally or not, it propagates some vision of the city and inspirations for its original design played an important role in it.

It’s not only about being inspired by this particular work: to make a city-building game, a lot of questions about our reality need to be asked.

Should building more roads help fight traffic jams? Should the city be divided into districts with different purposes (housing, industrial, etc.) or have a more dispersed structure? How important are parks and nature in the city?

This decision-making process is what politics is really about.

Laswell provides a great definition, claiming that politics is about who gets what, when, and how.

Politicians, elections, and debates are the most flashy elements of politics, but they are not the most important ones. Politics should be primarily understood as a process of deciding how a neighborhood, city, country, or even the world should look.

In that sense, games and politics have a lot in common. One may even say that politics is like game design but for reality. It’s a process of deciding which rules and activities should benefit the whole society.

And in that sense, games influence politics. These solutions come from society, which is shaped by culture. Games, like other media, are part of it. If the best method to fight traffic jams in SimCity is to build more roads, it’ll be more difficult to understand that in real life, it’s actually the opposite.

The degree to which a game is political varies from title to title. Some games are built around this topic, while others focus on things that have little to do with politics. Abstract puzzle games or sports games shouldn’t be put in the same basket as Metal Gear Solid or Bioshock. Tetris or FIFA aren’t political… right?

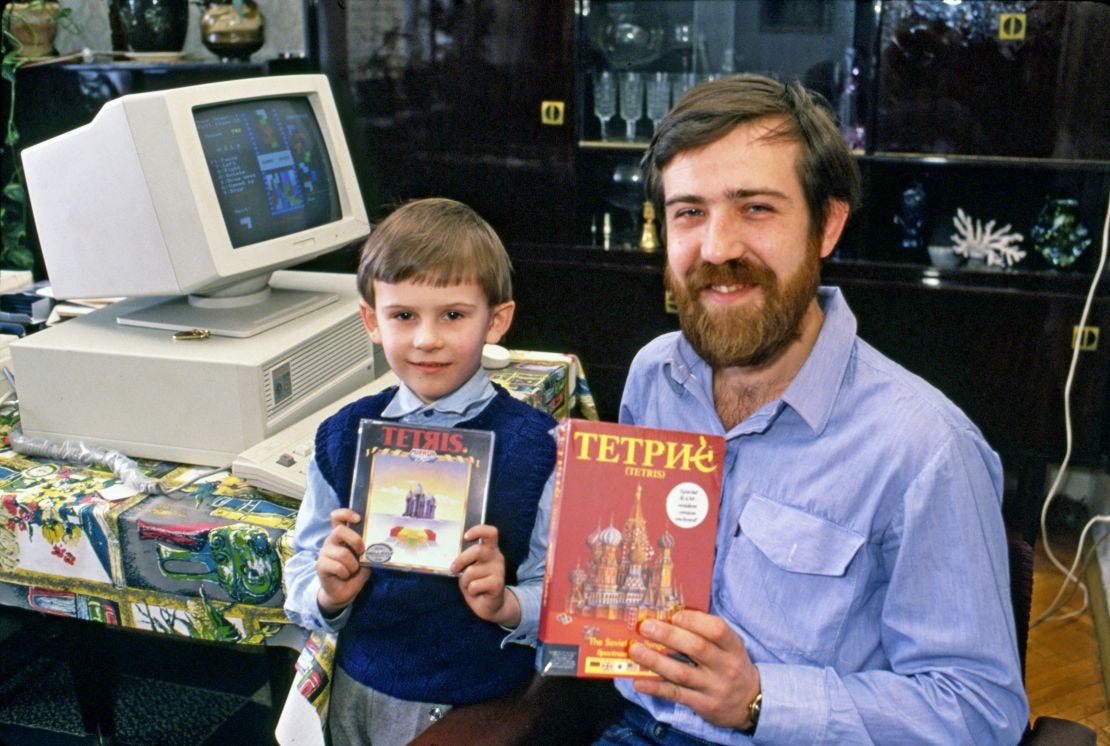

Well, maybe Tetris gameplay itself is quite abstract, but the issue of its commercial rights was quite a political entanglement: capitalist companies wanted to buy them from the communist Soviet Union, where the ingenious game about falling bricks was made by Aleksiej Pażytnow.

When Russia started a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, EA Sports removed the Russian national team and Russian football clubs from FIFA 22. It was a political act that was impossible to avoid. If they didn’t delete those teams, it would be perceived as pro-Russian activity as they were also banned in real-life international tournaments.

Most games have some sort of political message. It could have nothing to do with supporting liberal or conservative agendas, minorities, or feminism. If the game is any sort of trade, it speaks something about how the market works. Could you manage conflicts in the game by talking or fighting the only option? What is the most important to win - research, conquest, exploration? These matters are tightly connected with politics, even if that often happens subconsciously.

Games speak with mechanics. This concept was proposed by Ian Bogost in his book Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. He defines procedural rhetoric as:

“the art of persuasion through rule-based representations and interactions, rather than the spoken word, writing, images, or moving.”

In my opinion, it’s better to be conscious of the political impact of your game when making it instead of making a political stance by accident. It also makes your game better by touching topics that are relatable and important for people.

Citizen Sleeper is a clever text-based RPG with a bunch of interesting mechanics based on the strategic usage of dice and timers. The dystopian, cyberpunk setting is compelling and interesting to explore. However, what made me remember this game is how it shows the struggles of precarity. Despite being an android, the game's main hero is facing similar challenges that many people in our real world – living from one gig to another, hoping that it’ll bring enough money to pay for food, shelter, and medicines.

When playing Citizen Sleeper, I finally earned enough money to stop worrying about regular medical expenses, and I felt relief—a real one.

Citizen Sleeper shows how good games are at evoking empathy by putting players in someone’s shoes. Lucas Pope does the same kind of work in Papers, Please, another political game done right.

In this game, you work as an immigration inspector and check if people are allowed to cross the border to the fictional totalitarian country. The main conflict in the game comes from working for an oppressive regime that enforces ridiculous rules that make it difficulty to enter for a lot of people desperately needing to do so. On the other hand, your disobedience or mistakes may bring a terrible fate for your family that you try to maintain using your small salary.

As Soren Johnson noticed in his GDC talk:

“Through this tension, Papers Please gives players an understanding of why resistance against an oppressive system is so hard for people with real lives and, thus, why the powerful are able to stay in power.”

Putting politics in the center may help in creating a game that will be remembered for years. Like in the case of Bioshock, a game that shows how an attempt to build a utopian, libertarian society may end up. Irrational Games is a highly political game, but one that can stand next to dystopian classics like 1984 by Orwell or New Brave World by Huxley.

Politics in games is most efficient when players are encouraged to think about a particular topic instead of being preached about what opinion they should have. Games should provide a space to explore different political ideas, ask ethical questions, and reflect on how our world and society shape us.

Play as an activity was evolutionary serving this exact role: allowed to learn valuable skills in a limited environment. That’s why children's play often imitates very primal activities: fighting, exploring, building, etc. Games could serve as a space for learning different concepts, and politics may be one of them.

Making games that speak about politics by their mechanics is a powerful tool. But it also has its risks.

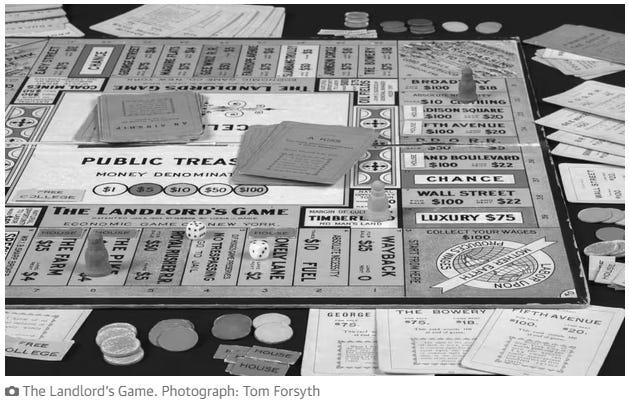

First of all, games always need to be engaging. I already told the story of The Landlord’s Game, but it’s worth repeating in this context. She described her game as “a practical demonstration of the present system of land-grabbing with all its usual outcomes and consequences."

Magie created two sets of rules:

One included tax, which rewards everybody when wealth is created. It was anti-monopolist in its intention.

The other one is about showing how monopolies crush all opponents.

Unfortunately, the second one was more engaging to play and was copied to make Monopoly, one of the most profitable board games ever made. The game's original message got lost, ultimately promoting the opposite perspective.

(I encourage you to read the whole article focused on the clash between creators' intentions vs. players' behavior here.)

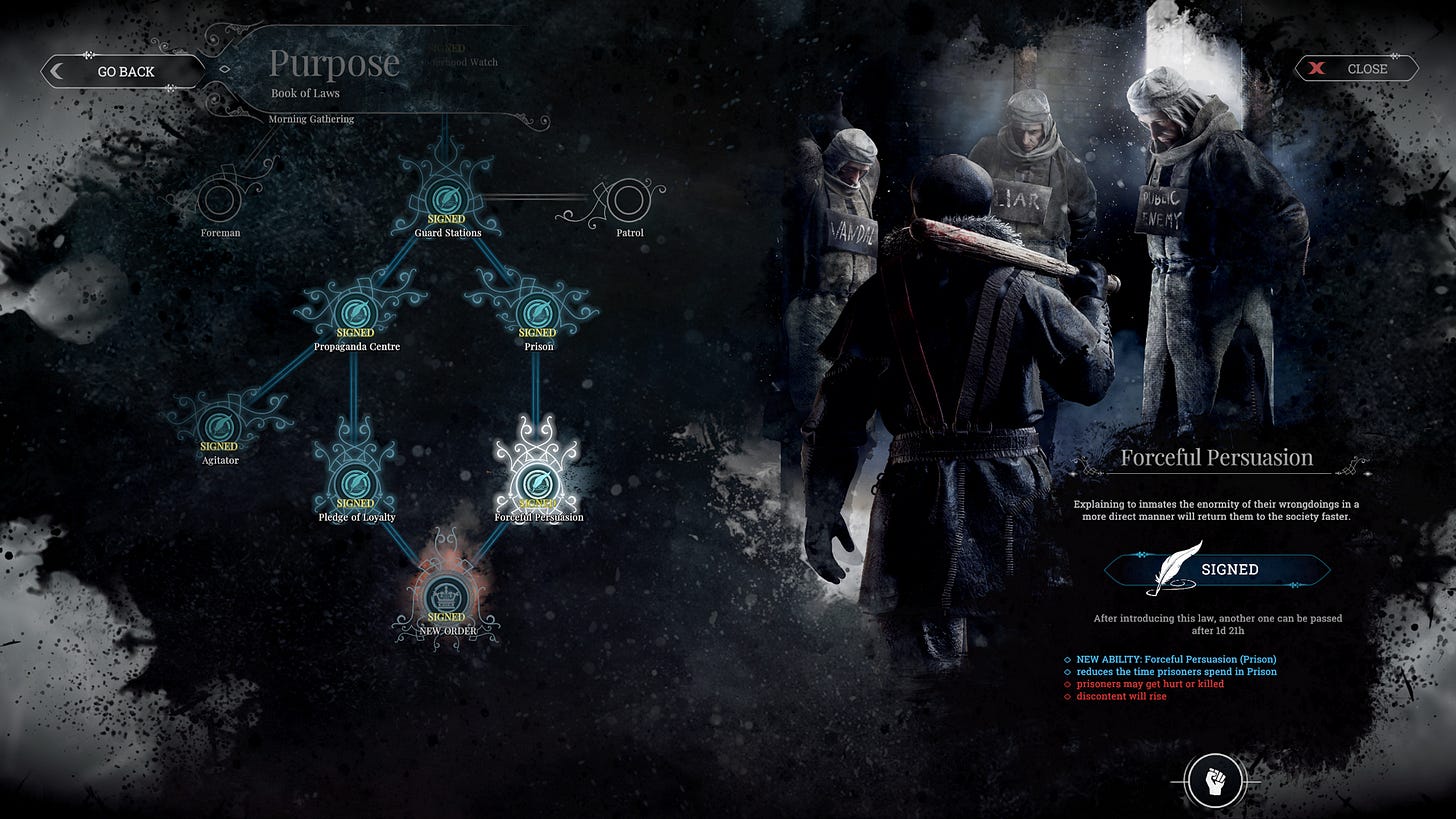

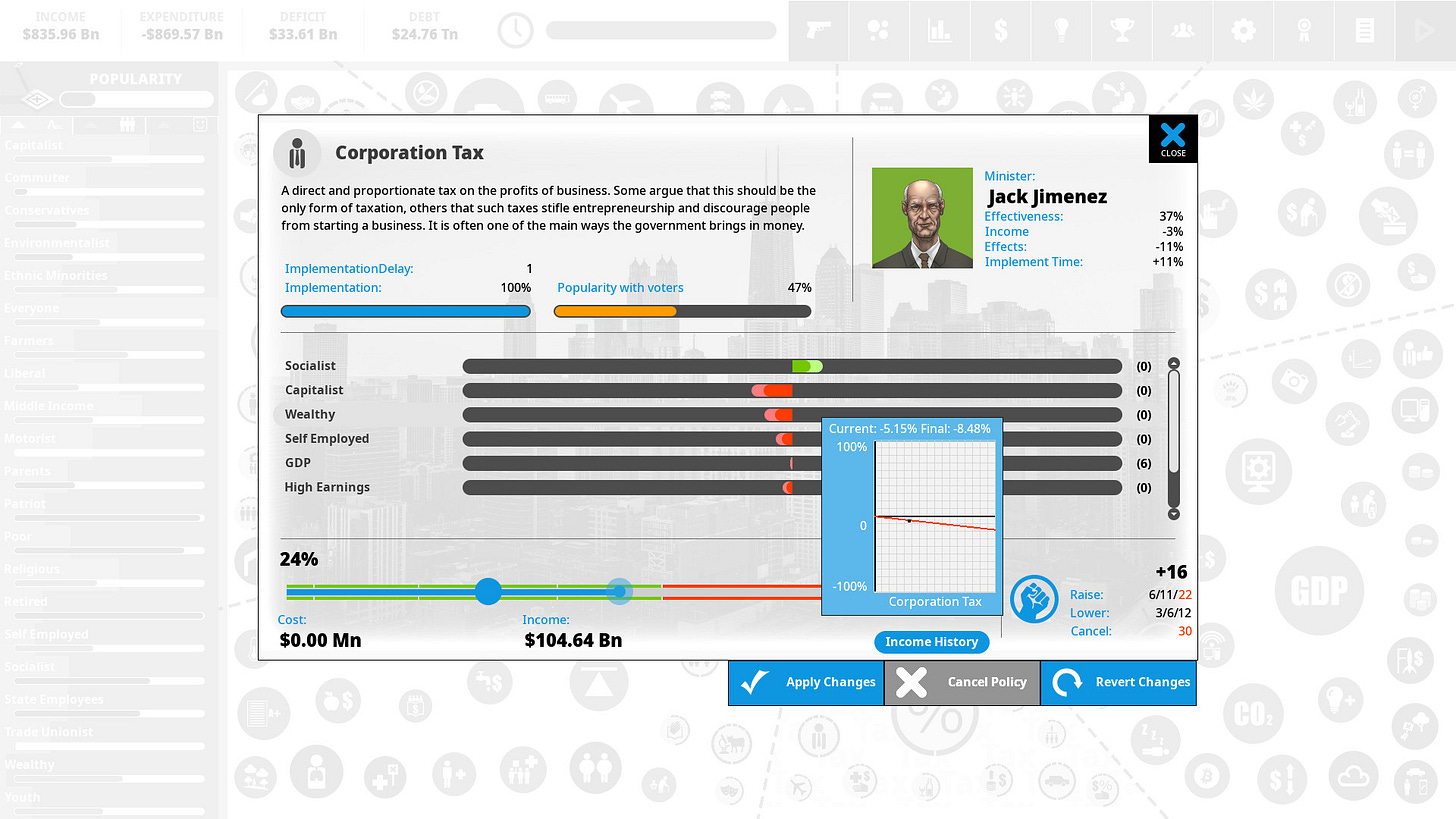

Another interesting example is Frostpunk, the game on which sequel I currently work. It’s how it’s described on Steam:

“Frostpunk is the first society survival game. As the ruler of the last city on Earth, it is your duty to manage both its citizens and infrastructure. What decisions will you make to ensure your society's survival? What will you do when pushed to breaking point? Who will you become in the process?”

Players may introduce laws that make survival easier but make the city more totalitarian, so the main question of the game is whether the end justifies the means.

While such a moral dilemma was relatable for a Western audience, the game was perceived differently in China. According to the South China Morning Post, some Chinese players were offended that the game suggested that they “crossed the line” in order to provide survivorship. From their cultural and political perception, the fate of the collective is far more important than the freedom of individuals, so the message of the game was different for them than for the creators.

However, making a game that ignites such debate and allows us to compare our worldviews may be perceived as a success. The more we do it in games, the more we will understand each other in the real world.

***

Today’s topic was inspired by a panel discussion about Games & Politics, in which I had the pleasure to be one of the panelists. You can listen to it here: